On a spring day in St. Louis, high schoolers from St. Joseph's Academy were making their way to the Columbia Bottom Conservation Area at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. These are the two largest rivers in North America, and the floodplain bears evidence of the powerful force of these waterways. The students were there to look for a problem that threatens even these formidable ecosystems - plastic pollution.

And it didn’t take them long to find it. “There were just bizarre things,” recalls Katie Lodes, a science teacher at St. Joseph’s who has been an educator for 33 years. Styrofoam pieces from coolers, sunglasses, shoes, fishing line, and beer cans. For Bailey Bryan, one of the students who volunteered for the cleanup, one item stuck out the most. “There was quite a bit that day… but the #1 thing that we found was cigarette butts.”

Bailey wasn’t alone in this finding. During the Mississippi River Plastic Pollution Initiative data collection in the spring of 2021, volunteers logged nearly 10,000 butts with Debris Tracker, making them the top item found in communities along the river.

The next semester Bailey would be enrolled in an Independent Research course. Katie created the course to let students explore their interests, and, in her words, “see how messy science is and how it never works out quite the way you think it’s going to work out.”

Bailey kept thinking about the cigarette butts she had found as she brainstormed ideas for her science project the next school year. “Based on my experience using Debris Tracker and the day that I went out to the confluence and was picking up cigarettes, I was just really intrigued by the topic idea of “What are the environmental impacts of cigarettes?” As she started reading articles on cigarette pollution, Bailey learned that butts can leach heavy metal compounds and arsenic into soil. Yet she still felt there was a gap. Bailey says there wasn’t “a lot of research looking at their impacts on organisms in their environments.”

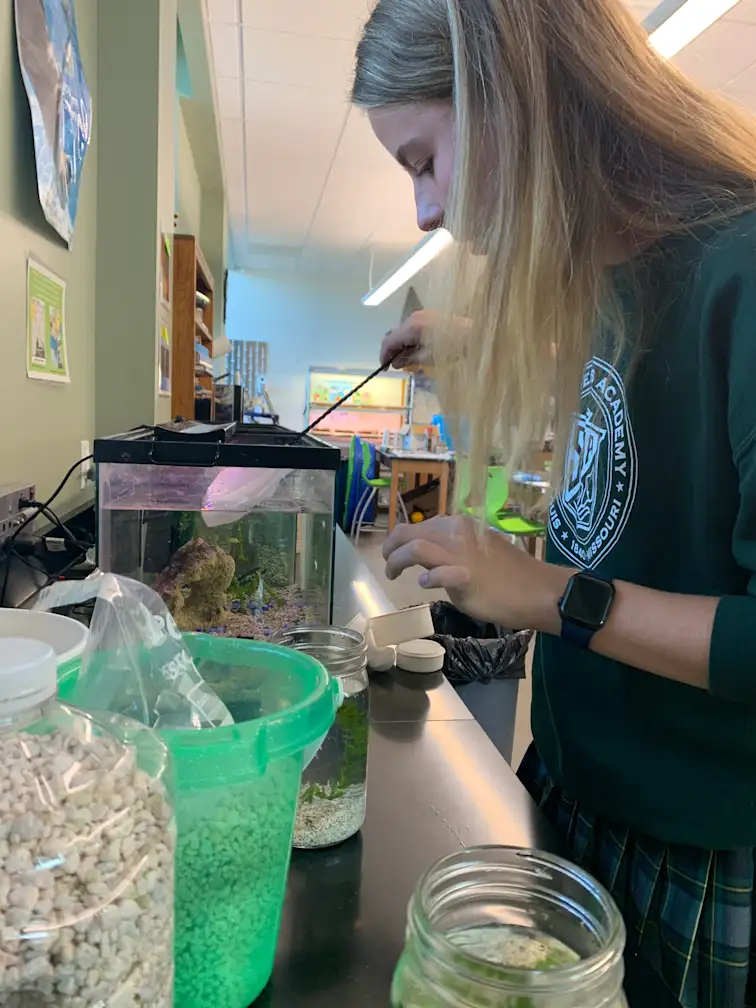

Bailey designed her experiment to study the impact of cigarette butt pollution on both an aquatic and terrestrial environment, by exposing ghost shrimp and bean plants to different amounts of cigarette butts.

But there was one problem. Safely getting used cigarette butts required a little bit of creativity. After some trial and error, Bailey cleverly thought of using syringes to “smoke” cigarettes under a fume hood, using the syringe to push and pull air through the cigarette as if a real person were smoking it. She recruited the science club to help “smoke” the cigarettes, to model used cigarette butts for her aquatic and terrestrial experiments.

Bailey says her experiments were a big learning process. “With the ghost shrimp, it was very much a visible impact right away. The ghost shrimp all sadly died immediately after adding the cigarettes to their tanks. There was lots of really good qualitative data with the ghost shrimp that I could see and write about in my log book.”

However, the bean plants were a different story. She was not seeing much difference in the control and experiment groups. “At first I was really frustrated about it and was really disappointed because I thought I was going to see something immediately. But a big thing that I learned and took away from that is that with research your first try is likely not going to yield results.”

Bailey plans to study biochemistry, and her hands-on experiments have yielded valuable lessons that she will carry forward into her future studies. Of her biggest learnings, Bailey says, “That’s how real research works - you make a modification, you try again, you look at what you could have done differently.”

Katie says other students have been brainstorming ways to use Debris Tracker and the data already collected to explore and study other items found in litter in St. Louis. “We’ve become big on citizen science, and we try to take those big datasets and find a local connection…I was just beyond thrilled that Bailey took it and ran with it.”